Peter Clarke is an extremely versatile artist, a book illustrator, a poet, a gifted writer of short stories, and a book-binder. As a printmaker he has been influenced by the prints of the German Expressionists and by Japanese woodcuts. He also has a strong interest in 20th-century Mexican artists such as Diego Rivera (1886–1957) and David Siqueiros (1896–1974). Their subject matter, with its strong social and political content and their depiction of ordinary people in a bold, naturalistic style, influenced his approach. Peter Clarke was a dock worker in the Simonstown dockyards before he became a full-time artist in 1956. For many years he has been intimately involved in the Cape Town arts community, organising many exhibitions and cultural events. His strong sense of social responsibility is evidenced by the fact that he has held art classes for local children for many years as well as acting as a mentor to aspiring artists. He has also been involved as an active supporter of a number of cultural organisations, particularly non-governmental organisations during the apartheid years.

The earliest work in the Campbell Smith Collection by Peter Clarke is a watercolour dated 1949 (plate 93) which is a gentle and lyrical evocation of a summer’s day at the beach along the False Bay coastline. The colour ink drawing of Two heads (plate 91), of just a year later, represents a significant development in his work. It has a sculptural solidity – Clarke’s knowledge of both Mexican and African art is readily apparent – and this was to become a feature of his figurative style in his subsequent work. In its sculptural stylisation it significantly pre-dates Gerard Sekoto’s ‘African’ heads of the 1960s and, more pertinently, Dumile Feni’s stylised ink drawings of the 1970s. When Campbell Smith first purchased the work he showed it to Clarke to see if the artist remembered it. Clarke smiled, disappeared upstairs and returned with a paper knife made from wood (plate 92). He explained that the figures in the double portrait were derived from whittling pieces of wood while employed as a dock worker in Simonstown.

His drawing Father and son (1957) (plate 81), illustrates the empathy and humanity which infuse his work. His fascination with masks stems from childhood memories of the festivities surrounding Guy Fawke’s Day – November 5th – in Cape Town. The masks worn by children, known as mombakkies, fascinated him, particularly in their variation in colour and design and the way that the masks disguised the individual. This strange, unknown persona is captured in the figure of the child in Father and Son. In the period from about 1954 to 1963 Peter Clarke depicted people wearing masks. It was in 1963 that he completed the engraving Girl with masks (plate 82). The works in the collection also illustrate Clarke’s intimate knowledge of the customs of people resident in the Cape Peninsula and all have a strong sense of place, rooted in the Cape and its immediate environs. In fact, Clarke’s work can also be seen as an invaluable social document celebrating both the joyous and the darker sides of life. An example of the latter is The chilum smokers (plate 79) (1975), which exposes the raw underbelly of life and drug taking on the Cape Flats in a manner matched by few other artists.

Joe Dolby

Born Simonstown, Cape, 1929. Training 1959: Michaelis School of Fine Art, University of Cape Town. 1959-1963: Rijks Academie van Beeldende Kunsten, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. 1976: Atelier Nord, Oslo, Norway. Selected exhibitions 1951 onwards : Group exhibitions South Africa, Germany, Brazil, Austria, Italy, The Netherlands, Belgium, USA, Argentina, Norway, Botswana, Japan, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. 1957: First solo exhibition, Oranje House, Cape Town. 1982: Exhibition of South African Art, National Gallery, Gaborone, Botswana. 1991: The Hand is the Tool of the Soul: Retrospective Exhibition, Iziko South African National Gallery / Natale Labia Museum, Cape Town. Collections Fisk University, Nashville, Tennesse, USA; Kunsthalle der Stadt, Bielefeld, Germany; Library of Congress, Washington DC, USA; National Gallery, Gaborone, Botswana; Stichting Afrika Museum, Bergen Dal, The Netherlands; Iziko South African National Gallery, Cape Town. Awards 1975: Honorary Fellow in Writing, University of Iowa, USA. 1982: Diploma of Merit in Art, Academia Italia. 1983: Honorary Member of the Museum of African American Art, Los Angeles, USA. 1982: Honorary Doctor of Literature, World Academy of Arts and Culture, Taipei, Taiwan.

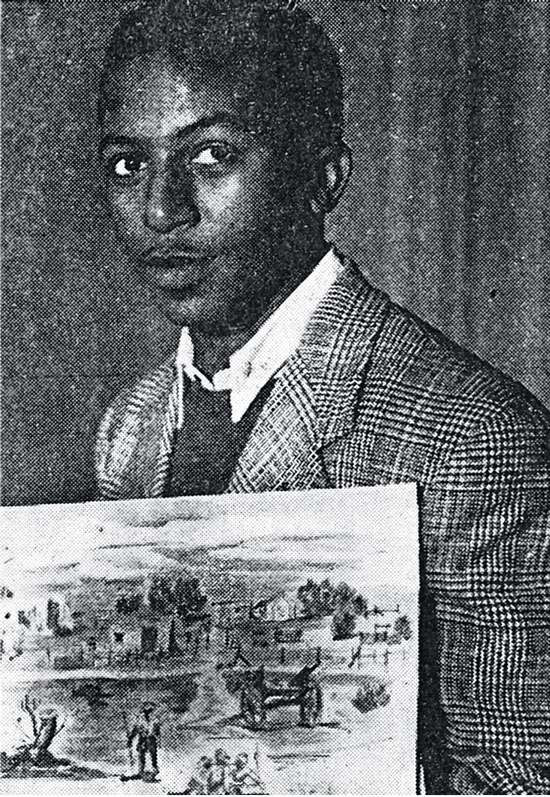

Peter Clarke, the Simonstown dockyard worker, with one of his sketches (right). Source: “Dockyard Worker plans career in Art”. The Cape Times, 24 June 1952. Photographer unknown. Peter Clarke outside his Ocean View home (left). Photograph by Bruce Campbell Smith.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Clarke’s preoccupation with graphic media, such as linocut, lithography, drawing and etching were often combined with his gifts as a writer and poet. Best known as a graphic artist, he drew extensively on subjects within his community. Esme Berman observed that his response to these subjects was ‘not a political commentary, but rather an observant, witty and compassionate response’. Clarke’s reputation as a painter was not generally known, although an oil by him was acquired by the William Humphreys Art Gallery in Kimberley, and also more recently by the Johannesburg Art Gallery. A number of his paintings are also to be seen in the Campbell Smith Collection.

The medium of gouache, essentially a more opaque form of watercolour, is typically part of the armoury of the graphic artist. Used mainly on paper, it is water-based and dries quickly. For Clarke, therefore, it has been a useful compromise between the slow-drying nature of oil paint, and the more limited colour range and the more labour- intensive techniques of graphic media. Fisherwoman with child, a work of 1960, shows how Clarke uses gouache to block in simplified forms in broad planes of colour, and to render such elements as the seagulls as deft strokes of his brush. Essentially an essay in contrasting areas of light and dark, the sky is rendered in tones of light and dark blue, and given a simplified structure, a process which is extended to the basic forms of the woman and the child. All of the elements in this picture, including the kelp on the beach, make this a quintessential image of the Cape.

Hayden Proud

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Peter Clarke (1929-2014):

Farewell to a quintessential artist of the Cape

Only this last Thursday I encountered Peter Clarke at the Iziko South African National Gallery, doing what he always enjoyed doing – looking intensely at an art exhibition. One of Peter’s own works, acquired by the Gallery in 1964, was featured on one of the current exhibitions. Peter had apparently been an intrepid visitor to the National Gallery over many years, even during the apartheid era when it was discomfiting and awkward for black visitors to frequent state-funded cultural institutions. Only a few years ago the Gallery acknowledged Peter’s artistic stature by staging a large retrospective of his work in conjunction with the Standard Bank Gallery in Johannesburg. Entitled “Listening to Distant Thunder: The Art of Peter Clarke”, it was curated by Philippa Hobbs and Elizabeth Rankin. The catalogue for the exhibition took the form of a large, well-illustrated book that quickly became a collector’s item. Fortunately, and apparently much to Peter’s delight, Hobbs and Rankin’s book is about to be republished as a second edition.

National acknowledgment for Peter was followed by exhibitions of his work in London, and, most recently, last year, in Paris. Peter’s dapper and familiar figure were known to the entire South African art community and, despite the fact that he was well in his eighties, his energy and his outlook made this hard to believe.

Peter was an incredibly humble and hard-working artist and poet whose life and work were centred upon his community in Simon’s Town and eventually Ocean View, to where he and his family were forcibly moved under the Group Areas Act. He lived and breathed for his community. And yet, despite having his life corralled into an apartheid-constructed ghetto, his outlook reached far beyond the Cape Peninsula and South Africa’s strictures to embrace the wider world. His paintings, prints and drawings, surprisingly, were without any reflection of rancour or bitterness. Instead, with a loving and acutely perceptive eye, he recorded, as perhaps no other artist ever has, the realities and the humour of life as it is lived in the Cape by the majority of its inhabitants. Peter was every inch a gentleman at all times, and his conversation was always sharp, informed and full of wit. He was that rara avis – a truly well-read artist. If Johannesburg had an artistic hero in Gerard Sekoto, and Port Elizabeth has its in George Pemba, the equivalent place of honour in the Western Cape must surely and justly belong to nobody else but Peter Clarke.

I engaged Peter in conversation and warmly shook his hand as we parted, little realizing that this would be the very last time that I – or the National Gallery – would ever see his familiar figure again. Peter died peacefully at his home in Ocean View this morning.

In him, Cape Town has lost one of its greatest sons, and young South Africans have lost an incredible role model.

Hayden Proud

13th April, 2014